Saving Earth’s Last Primary Forests

Earth’s spectacular primary forests are unique and irreplaceable ecosystems, unmatched in their ability to provide ecosystem services as nature-based solutions. They are very often the homelands of Indigenous Peoples, essential to Indigenous cultures and local livelihoods.

Primary forests include over two thirds of the planet’s land and freshwater species, and countless endangered species, they fight climate change by storing vast amounts of carbon and drawing down carbon from the atmosphere, ensure reliable, high quality drinking water, and may also function as natural quarantine areas by limiting the spread of zoonotic diseases like COVID19. Primary forests are therefore essential life-support systems, critical to addressing many of our most urgent environmental and social problems.

But they are going fast. We’ve already lost over a third of Earth’s forests, less than a third of our remaining forests are primary, and we lose millions of hectares of primary forest each year. We urgently need to protect our remaining primary forests, large or small! Even small patches are important: they are critical building blocks because they provide the seed banks and seed dispersers (birds, pigs, monkeys etc.) we need to bring forests back.

Get Educated

A primary forest is a forest that is the result of natural processes rather than human management, and that has not been degraded by industrial activities. Mature trees often dominate the forest canopy and a primary forest contains most or all of its native plant and animal species. Primary forests include all successional age classes (young to old-growth), including primary forests regenerating after wildfire and other natural disturbances.

More specifically, a primary forest is a forest whose vegetation structure, species composition and ecosystem dynamics are predominantly the product of natural physical, ecological and evolutionary processes, including natural disturbance regimes such as fires, storms, floods, insects, and landslides. Primary forests retain most if not all of their evolved, characteristic native plant, animal and microbial species, have few if any invasive species, are often dominated at the landscape scale by mature canopy trees, contain many large dead standing (snags) and down (logs) trees, and have not been subject to industrial land use activities such as commercial logging, mining or ranching.

As a “chapeau” term, primary forest covers a range of related terms including “old-growth forest”, “ancient forest,” “primeval forest,” and “intact forest landscapes.”

Primary forests ensure a wide range of vital ecosystem services that are either unique, or are of a superior quality and quantity to degraded forests, secondary re-growth forests, or plantations. In particular, they:

- Protect the most biodiversity (plant, animal and invertebrate species) – at least two thirds of the planet’s terrestrial and freshwater species are found in primary forests;

- Store 35-70% more carbon than degraded forests or plantations and their carbon stocks are more stable because primary forests are more resistant to change, and more resilient when natural change inevitably happens. To avoid dangerous climate change, we must protect the massive carbon stocks already accumulated in primary forests.

- Provide the cleanest freshwater, prevent erosion and help regulate local water cycles.

- May prevent the spread of zoonotic disease to humans. Deforestation and degradation of primary forests and associated road building (e.g. logging or mining roads) often enables bushmeat trade and wildlife trafficking and facilitates disease transmission to humans.

- Many are homelands of Indigenous Peoples that are crucial for sustaining traditional cultures and community livelihoods. Primary forests often remain in good condition because of Indigenous and community stewardship.

Importantly, primary forests provide more and higher quality ecosystem services because of their higher levels of biodiversity and ecosystem integrity. To protect a primary forest’s ability to provide its full range of benefits it is critical to protect it from inappropriate land use activities, including industrial disturbance.

The world already has lost over a third (about 35%) of the planet’s pre-agricultural primary forests. Just over a quarter (27% or 1.1 billion ha) of the world’s forests remain in a primary forest condition.

Source: Mackey et al. 2014. Policy Options for the World’s Primary Forests in Multilateral Environmental Agreements. Conservation Letters https://conbio.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/conl.12120

According to the UN’s Food and Agriculture Organization we are losing about 4 million hectares per year, though FAO statistics on primary forests significantly underestimate loss because the government reports they are based on are not always reliable and some governments do not report on primary forest loss at all. The recent scientific literature suggests that forests are being fragmented and degraded at very high rates. For example, a study in 2015 found that 70% of the world’s forests were now within one kilometer of a forest edge (road, clearing, pipeline etc.). A 2017 study found that large, contiguous blocks of forest (50,000 hectares or more) had decreased by over 7% since the year 2000.

Industrial agriculture is a primary driver of deforestation globally, including of primary forests. Primary forests are being cleared to make room for crops such as palm oil, soy etc. and for cattle ranching. Oil and gas extraction and mining also contribute to deforestation, as do large-scale infrastructure such as roads and hydropower projects.

Primary forests are also being degraded primarily by commercial logging and by fuelwood gathering. Despite decades of efforts to develop best-practices for the logging industry, commercial logging has not proven sustainable in primary forests and often leads to total deforestation as degraded forests whose valuable timber has been removed are converted to agriculture.

In many regions, growing human populations are expanding the footprint of slash and burn agriculture. Helping communities farm more sustainably and develop alternative development pathways based on forest conservation is a prerequisite for protecting the world’s remaining primary forests.

We know the range of mechanisms that are effective at protecting primary forests. Protected areas with good governance and adequate funding can successfully protect primary forests. Similarly, community conservation initiatives and Indigenous peoples have a proven track record of protecting primary forests – often over millennia. Payments for ecosystem services schemes have also met with success. Conversely, it is crucial to stop viewing commercial logging as a sustainable and viable solution for protecting primary forests. Commercial logging has not proven sustainable in primary forests anywhere.

We need to “flip” incentive structures so that national and multilateral subsidies are directed to mechanisms that have demonstrated capacity to achieve primary forest protection – and to restoring degraded forest or regenerating forest. Currently, subsidies for industrial agriculture, extractive industries and other industrial developments far outweigh conservation funding. Shifting this balance to support actors on the ground that have a commitment and vested interest in keeping primary forests standing – especially indigenous and local communities – can have a profound and rapid effect on primary forest protection globally.

Watch these videos to learn more about Primary Forests

Our Initiatives

International

Wild Heritage advocates for making primary forests a key focus in the UN Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD), the key treaty guiding global nature conservation efforts.

WE MADE MAJOR BREAKTHROUGHS AT COP15 in December 2022!

In 2018 at the CBD’s 14th Conference of the Parties (COP14) in Sharm El-Sheikh, Egypt, we worked closely with the Government of Costa Rica to champion text on primary forests and ecosystem integrity in the CBD. Amazingly, prior to 2018 primary forests had never been mentioned as a key priority in the CBD but we managed to change that with CBD Decisions 14/5 and 14/30, which still stand a major policy milestone and critically important precedent.

In 2022 we returned to the CBD for COP15 in Montreal. This was one of the most important nature conservation summits in decades, as the international community was gathering to agree on a new global conservation strategy – the Global Biodiversity Framework – which will guide conservation efforts around the world through 2050. We went to Montreal to help ensure that ecosystem integrity was clearly included as a core principle in the CBD’s GBF. We were able to do so, creating a strong international mandate for protecting primary forests and other high integrity ecosystems.

Another major victory at COP15 was that we were able to work with indigenous partners (in particular COICA and Amazonia for Life) to include indigenous territories as a separate conservation category in the Global Biodiversity Framework. Recognizing the essential contribution that indigenous peoples make to global conservation efforts, without requiring them to redefine their lands as protected areas, was important progress. This should also facilitate getting international funding directly to indigenous peoples for their critically important conservation stewardship.

We also launched the Primary Forest Alliance at COP15, calling for a moratorium on industrial logging in primary forests. Over 160 organizations have now joined the PFA, and the coalition continues to grow. Please visit the Primary Forest Alliance website for more information and please watch our video!

We also made a strong push for the CBD and the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change to work more closely together. This is fundamental as the climate and biodiversity crises are so closely related. We didn’t make much progress in Montreal…but almost a year later we had a major breakthrough on this issue in Dubai! Please see below.

Wild Heritage has been working with partners (in particular the Australian Rainforest Conservation Society) to raise awareness in the UNFCCC of the importance of primary forests as a climate change solution, and in particular to help ensure that the CBD and the UNFCCC work synergistically on strategy and funding priorities (for more information, please see this report, this policy brief and the F20 Nexus Report below).

This idea has been rapidly gaining momentum over the last year…and took off at the UNFCCC’s climate COP in Dubai in 2023 with the COP28 Joint Statement on Climate, Nature and People and the UNFCCC’s Global stocktake decision which both contain text very close to what we have been promoting for several years.

The new political consensus to bring the CBD and UNFCCC closer together so they work more synergistically is a major development. It should make it easier to direct large scale climate funding to primary forests, and the indigenous peoples who protect them. We have a lot of work to do to make the Joint Statement and the global stocktake a reality on the ground, but this is an important step and a win for primary forests!

Wild Heritage played a key role in successfully advocating for a GEF funding window on primary forests. This new funding program, called the Critical Forest Biomes Integrated Program, will distribute $300m over four years for primary forest protection projects around the world. This was a huge breakthrough (which we celebrated in Montreal at the biodiversity summit) and has provided an immediate and much needed injection of funds to governments and NGOs for primary forest protection.

We have been in discussions with the GEF over the last year on how to build on this great result. What has emerged is a tremendously exciting $2.2m project involving the UN Forum on Forests (UNFF), the UN Food and Agriculture Organization, the International Union for Conservation of Nature, Wild Heritage and Griffith University (Australia) on how to better integrate primary forests into international policy. We are in the final stages of project design and hope to be able to start work early next year. Wild Heritage and Griffith would get roughly a third of the project funding, and even more importantly this project would put us in the middle of UN forest policy discussions. There was a soft launch of this project in Dubai at the climate summit on December 8 featuring Juliette Biao, the Director of the UNFF, Garo Batmanian, General Director of the Brazilian Forestry Service and Prof. Brendan Mackey (Griffith Univ.), one of our closest colleagues, where we also launched a report and policy brief. This is an especially important project for us as discussions on how to protect the world’s forests take center stage over the next few years, first as the UNFF reviews the UN’s forest policy framework in 2024, and then as the CBD meets at COP16 in Colombia and the UNFCCC meets at COP 30 in Brazil’s Amazon region in 2025.

Wild Heritage continues to serve on the Amazonia for Life Steering Committee in partnership with COICA, Stand.earth and others. Nearly 1,000 organizations have now signed the Amazonia for Life declaration, which calls for protecting 80% of Amazonia (50% is already protected) to avoid reaching tipping points where Amazonian forests begin to convert to dry, savanna ecosystems. Our initiative hit two big milestones this year. The first was recognition by the UN Permanent Forum on Indigenous Issues at its 22nd session in April in New York City. The second was an official endorsement by the Government of Colombia at the recent Amazon Summit in Brazil in August. The CBD summit in Colombia next year, and the UNFCCC summit in 2025 as critical gatherings for this initiative.

See: The Nexus Report: Nature Based Solutions to the Biodiversity and Climate Crisis commissioned by the Wyss Campaign for Nature (US) and the Society of Entrepreneurs and Ecology (China), which strongly emphasizes the importance of primary forests and the climate-biodiversity nexus.

Wild Heritage Executive Director Cyril Kormos drafted several IUCN resolutions calling for an IUCN primary forest policy over the last decade, and was a member of the IUCN Primary Forest Task Team which ultimately came together to write IUCN’s primary forest policy. The policy was approved in 2021 and now guides IUCN’s 1,300 organizational members and 13,000 volunteer IUCN Commission experts in their work. See IUCN’s Crossroads blog, Primary Forest Policy and primary forests story map.

Our close working partner Wild Europe (Cyril Kormos sits on the Wild Europe Executive Committee) was instrumental in bringing about a new policy in Europe calling for protection of remaining primary forests in Europe. Sadly little primary forest remains – the goal now is to ensure that the little that does is strictly protected, and that ecological restoration occurs around these remaining primary forest fragments to buffer and reconnect them and rebuild larger and more robust forest ecosystems.

North America

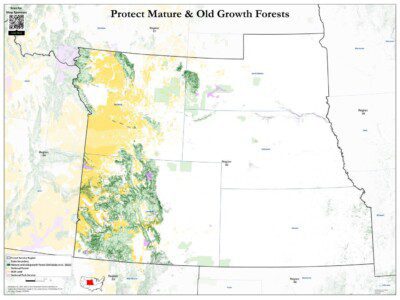

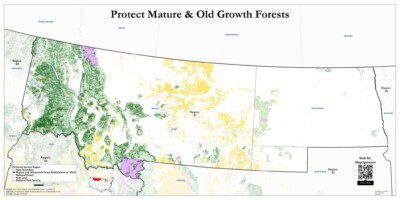

In the United States, most primary, old-growth forests were logged decades-centuries ago as forests were cleared and degraded as the country expanded. We must protect the old-growth forests we have left while working to recover these endangered ecosystems over time by also protecting mature forests that are the building blocks to restore old growth. This also means that when older forests experience natural disturbances such as wildfires and insect outbreaks they should be allowed to rejuvenate and reset forest successional processes without logging them.

On Earth Day 2022, President Biden initiated a public process to define and inventory mature and old-growth forests for possible protections. Wild Heritage and our partners Griffith University (Australia), NatureServe, and Woodwell Climate Research Center (Massachusetts) published the first-ever inventory of mature and old-growth forests in the continental US that compliments our old-growth forest mapping publication for the Tongass rainforest in Alaska. We are delivering all our science products to the Biden administration during the public review of mature forest policy options and in support of the climate-forest.org coalition and forestcarboncoalition.org that have requested the federal government act by conducting national rulemaking similar to what was done for the roadless conservation rule in 2000.

MEDIA LINKS:

Photo: Fraser River, inland temperate rainforest, BC (D. DellaSala)

One of the world’s rarest and most imperiled rainforests is pressed against the windward toe-slopes of the Canadian Rocky Mountains, the nearest town is Prince George, BC, a 90 minute flight east of Vancouver. Since 2018, Wild Heritage has been partnering with regional scientists and local activists (conservationnorth.org) in calling attention to this “forgotten rainforest.” And, while Canada’s coastal Great Bear Rainforest has 84% of the region in some form of protection, its inland rainforest has been exposed to rampant logging that threatens to unravel the ecosystem within a decade or so based on analysis we did using the IUCN’s Red-listed Ecosystem Status assessment. Together with our partners at the University of Northern BC, Griffith University in Australia, the Conservation Biology Institute in Corvallis, and Conservation North, we have been spotlighting the region’s precarious plight in science journals, the press, and with the BC government. An emerging regional threat is logging within primary forests to produce wood pellets for shipping overseas to the UK where it is being marketed by Drax (biomass pellet plant) as “clean, renewable, energy.” This tragic waste of a world-class rainforest for “clean energy” along with ongoing logging in general may trigger ecosystem collapse within a decade if these forests are not protected in collaboration with First Nations. MEDIA LINKS:- https://esajournals.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1002/ecs2.4020

- Increased logging endangers rainforests in B.C.’s Interior, study says – https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/british-columbia/interior-wet-belt-interior-temperate-rainforest-1.5800915;

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=nqUCyMxvN9Y;

- https://thenarwhal.ca/bc-old-growth-inland-rainforest-study-2021/;

- https://php.radford.edu/~swoodwar/biomes/?page_id=2286

- Conservation North – https://conservationnorth.org/interior-rainforest-logging-is-exacerbating-global-climate-change/

- Standwithus4oldgrowth- https://www.standwithus4oldgrowth.org/

- Yellowstone to Yukon – https://y2y.net/blog/research-brief-ecosystem-services-and-british-columbias-inland-temperate-rainforest/

- Scientists call to action – https://the-peak.ca/2018/07/hundreds-of-international-scientists-call-for-urgent-action-to-protect-b-cs-rainforests/

- Link to news bulletin – https://www.kimberleybulletin.com/news/evidence-of-logging-cutting-permits-in-proposed-old-growth-deferrals-wildsight/

- Valhalla Wilderness Society – https://www.vws.org/project/inland/TheInlandRainforest.html

- Cascadia story – https://www.cascadiamagazine.org/features/clear-cut-saving-bcs-inland-rainforest/

- Raincoast – https://www.raincoast.org/2010/11/scientists-urge-rainforest-protection

Wild Heritage’s focuses on four regions known for extraordinary biodiversity and carbon storage as natural climate solutions: (1) Greater Pacific Northwest, (2) Sierra, (3) Klamath-Siskiyou, and (4) Tongass (rainforest).

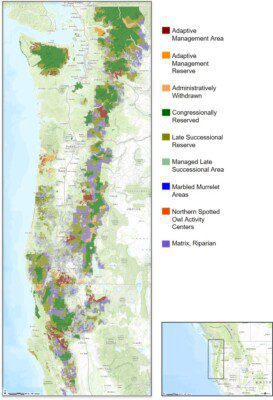

Greater Pacific Northwest Bioregion

This expansive bioregion extends from northern California to Washington, spanning both wet forests west of the Cascade Crest, and dry, fire-dependent forests east of the Cascade Crest. Several smaller ecoregions are nested within, some of which are recognized as WWF Global 200 ecoregions (Klamath-Siskiyou) for their world-class biodiversity. The amount of carbon stored in Pacific Northwest forests (coastal) is significant on a global scale and needs to be protected from logging for climate and biodiversity benefits. Importantly, the Northwest Forest Plan is a global model of biodiversity conservation and ecosystem management on 10 million hectares (25 million acres) of federal lands with roughly one-third of the forests in forest reserves (i.e., late-successional reserves – LSRs) anchored on recovery of the federally threatened Northern Spotted Owl, Marbled Murrelet, and Coho Salmon. The plan may soon be revised by the USDA Forest Service and there are efforts underway to undermine protections that we have been pushing back on.

Wild Heritage has an extensive track record of working in this region dating back decades of conservation via Dr. DellaSala’s lead science role. We are currently providing technical expertise to local conservation groups pushing back on logging in mature forests and fighting to restore protection of large trees in dry forest forests in eastern Oregon and Washington. Under the Trump Administration, the so-called “Eastside Screens” that protected large trees for over two decades were removed and trees up to 150 yrs old can now be logged. We are working with local and regional groups to restore them.

MEDIA LINKS:

- Mature/Old Growth National Assessment – https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/ffgc.2022.979528/full

- Mature Old Forests Importance – https://news.mongabay.com/2022/10/new-study-identifies-mature-forests-on-u-s-federal-lands-ripe-for-protection/

- Strategic carbon reserves for older forests – https://www.seattletimes.com/opinion/a-strategic-natural-carbon-reserve-to-fight-climate-change/

- End mature/old growth logging on federal lands – https://www.ijpr.org/show/the-jefferson-exchange/2022-10-04/wed-8-30-researchers-make-a-map-of-all-old-growth-forest-in-lower-48;

- https://www.ijpr.org/show/the-jefferson-exchange/2021-11-01/tue-8-am-rogue-valley-scientist-proposes-an-end-to-logging-of-older-u-s-forests

- https://thehill.com/opinion/energy-environment/581612-us-forests-hold-climate-keys/

- Climate importance of older forests – https://news.mongabay.com/2021/11/as-fossil-fuel-use-surges-will-cop26-protect-forests-to-slow-climate-change/

- http://www.justincatanoso.com/2021/09/01/mongabay-old-growth-forests-of-pacific-northwest-could-be-key-to-climate-action-story-and-video/;

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=KamQ6NY7HK0

- Importance of reserves in the Northwest Forest Plan – https://www.mdpi.com/1999-4907/6/9/3326

- Importance of NW Forests for carbon – https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/24894007/

- Importance of large trees in dry forests of Oregon/Washington – https://oregonwild.org/sites/default/files/pdf-files/Large%20Trees%20Report%20resize.pdf

- Importance of Klamath-Siskiyou as climate sanctuary – https://www.researchgate.net/publication/259576813_Climate_Change_Refugia_for_Biodiversity_in_the_Klamath-Siskiyou_Ecoregion

- Importance of Sierra Nevada dry forests and mixed-severity fire association – https://fireecology.springeropen.com/articles/10.4996/fireecology.130248173

Photo: Tongass rainforest, Alaska (D. DellaSala)

Photo: Tongass rainforest, Alaska (D. DellaSala) This nearly 7 million hectare (16.8 M ac) national forest is the crown-jewel of the USDA National Forest system. Ancient cedars and hemlocks tower to its Alaska skyline. Prolific salmon line up to spawn in pristine streams that resemble rush hour traffic jams. Brown bears, wolves, and bald eagles feed on spawned out salmon carcasses that also supply critical nutrients to rainforest trees via decomposition and absorption of minerals. This single national forest contains the largest concentration of old-growth forests (~2 million ha, 5 million acres) in the nation, the largest concentration of Inventoried Roadless Areas (IRAs, 3.72 M ha, 9.3M ac), representing 16% of the nation’s total IRAs, and contains the equivalent of 20% of all the carbon stored across the entire national forest system, mostly within old-growth forests and IRAs. It is truly a remarkable forest and one of the world’s last remaining intact temperate rainforests.

Wild Heritage Chief Scientist Dominick DellaSala has a three-decade history of working in the Tongass from some of the first wildlife surveys to forest carbon accounting. The Tongass also has a long political history of massive logging ushered in during the 1950s logging for pulp that continued for half a century. In 2016, at the urging of Wild Heritage staff and partners, the Obama Administration announced a transition out of old-growth logging and into naturally reforested sites now commercially available for supporting timber needs without cutting old-growth forests. At the time, the administration believed it would take decades to facilitate a transition, so we showed them how to do it within years. Unfortunately, the Trump Administration reversed course, pulling the plug on transition, and removing protections for old-growth forests and IRAs. They faced stiff opposition from scientists, conservation groups, and Alaskan tribes.

The Biden Administration announced in 2021 that it would restore IRA protections and put the transition to young forests back on track as part of its southeast Alaska sustainability initiative. And while most logging has currently shifted out of old-growth forests, the roadless policy has yet to be fully reinstated, which we anticipate will happen in 2022.

Chief scientist Dominick DellaSala explains the importance of one of the world’s rarest temperate rainforests in this live Facebook event.

Read letter from Wild Heritage

MEDIA LINKS:

- Tongass rainforest is globally important – https://alaska-native-news.com/tongass-rainforest-in-alaska-is-a-carbon-sink-of-global-importance/61535/

- End old-growth logging on Tongass – https://www.hatchmag.com/articles/permanently-end-old-growth-logging-americas-salmon-forest/7715509;

- https://news.mongabay.com/2022/06/end-old-growth-logging-in-carbon-rich-crown-jewel-of-u-s-forests-study/

- Climate responsible forest management on the Tongass – https://www.adn.com/opinions/2022/06/13/opinion-the-tongass-can-be-a-world-leader-in-climate-responsible-forestry/

- Carbon rich Tongass rainforest – https://news.mongabay.com/2022/06/end-old-growth-logging-in-carbon-rich-crown-jewel-of-u-s-forests-study/

- Tongass as a world-class carbon sink – https://www.mdpi.com/2073-445X/11/5/717

- Biden Bans Roads and Logging in Alaska’s Tongass National Forest – https://wild-heritage.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/02/Biden-Bans-Roads-and-Logging-in-Alaskas-Tongass-National-Forest__NYT_25Jan23.pdf